Nick Modrzewski recently spoke with COMA director Sotiris Sotiriou about his current exhibition with the gallery, The Plaintiff’s Third Face. In the conversation the two unpack the presentation and its roots in medieval history, absurdism and the theatricality of the legal system.

Sotiris Sotiriou: Your exhibition text states “to exist in the legal system, a series of ‘faces’, disguises or masks must be worn”. In this context, can you expand upon the actual title itself – The Plaintiff’s Third Face?

Nick Modrzewski: Sure. The title is taken from a pretend judgment that I wrote for the show, called Beckshire v Handleman. The full judgment, by an imagined Judge called “Justice Ortold”, appears in the form of a long scroll that hangs above the mantle in Gallery 2. At one point in the judgment, the judge is describing the way in which the Plaintiff’s face keeps changing during the court hearing. The Plaintiff starts by wearing “The Face of Credibility and Reliability”, which has a smooth and generally pleasant appearance, before shifting to “The Face of the Wronged Complainant”, which likewise appears to be a rustic and noble face. However, the Judge observes that neither of these two faces fit the Plaintiff very well. When the Plaintiff is eventually cross-examined by the Defendant’s barrister, the Plaintiff starts sweating and both faces slip down the Plaintiff’s forehead, revealing a “third” face. This is what the Judge says about it:

“What lay beneath was a very different face indeed: the shape of the eyebrows appeared to be carved out with a hacksaw, the nose was elongated and covered in what appeared to be boils and the mouth was crinkled into something of a contrived hole. I will refer to the Plaintiff’s third face as the Face of the Unveiled Fraudster. The Plaintiff’s entire appearance seemed to shift with the revelation of the Face of the Unveiled Fraudster. His voice became shrill, unpredictable, looping in on itself and crying out at unexpected moments.”

So, the title of the show, The Plaintiff’s Third Face, speaks to this experience of appearing before the law and the way that different guises are either intentionally worn, or imposed on us by legal processes. And the law can cast us as a host of different characters. For instance, if you’re the defendant in a court case and you lose the case, you’re likely to be ordered to pay a sum of money to the plaintiff. So, the court classifies you as a “judgment debtor”, meaning that you owe a debt to the plaintiff. You literally become this “judgment debtor” character in the eyes of the law. And this “character” has a history – it has appeared for hundreds of years in legal textbooks and judgments and courtrooms across the world. There is a whole universe of intertextual legal and cultural references that establish who this character is. But there are also real-life consequences of being a judgment debtor – there are coercive measures that the court can take to force you to play your “role”, like ordering the sheriff to seize your assets, or ordering that a portion of your income is re-directed to the Plaintiff.

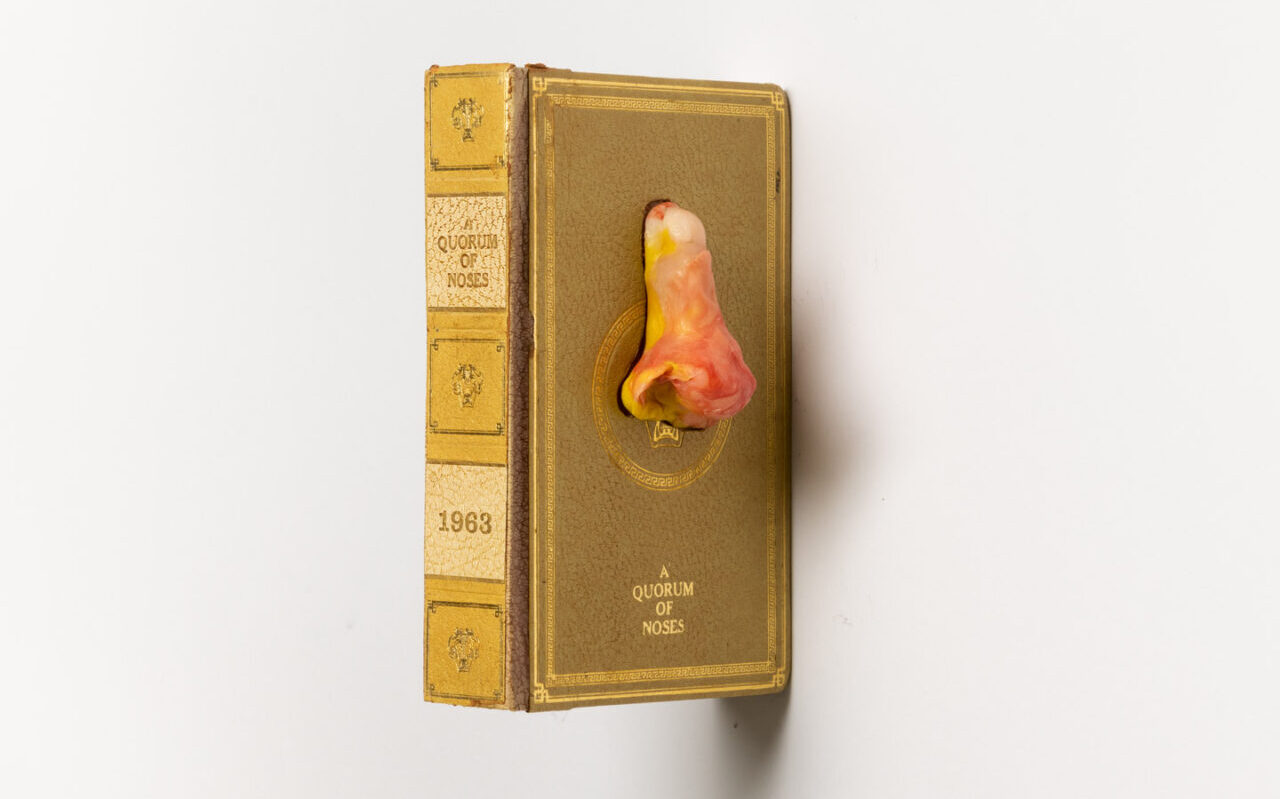

The centrepiece of the show is a wall of 56 sculptural masks, each one referencing different legal faces. You can see the Plaintiff’s third face, The Face of the Unveiled Fraudster, up there. There’s also The Swamp-Mucked Face of a Junior Associate (Magistrates’ Court), The Face of Executive Government and The Leather Tongued, Multi-Layered Face of an Onion Grower During Evidence-In-Chief. And then there are other faces with more abstract relationships to law, like the Face of a Small Gathering of Noses. Justice Ortold makes an appearance too.

SS: There are lots of historical references in The Plaintiff’s Third Face that allow the viewer to contemplate different time periods and modes of living. There are drawings on aged paper, an ancient-looking scroll and an axe and sword on the wall. While these works are often linked to legal histories, it seems there is an inevitable drifting away from legal issues. Is this something you want out of your work – incursions into other areas of human history and interaction?

NM: Absolutely. The show is grounded in “the legal”, but this is only a starting point. For me, the law is this resource of inspiration. It’s an ever-evolving document of human folly and disaster and triumph and drama and absurdity. I’m constantly drawing on legal resources for the conceptual grounding of my work. But my studio practice is very physical and intuitive and playful. It’s very much grounded in “making”. I might start with a specific idea, like “the Corporations Act”, but I’m careful not to constrain the process. I’m always responding to each work in a sensual, physical (rather than purely cerebral) way. I’ll let my hands and mind rove into all sorts of other territories, beyond the initial legal idea. Because for me, the studio is this slippery place where borders and categories tend to collapse and I’m able to find all these unexpected links between disparate ideas. So it’s inevitable that there are incursions into other histories and areas beyond the law. It was through thinking about law as this form of verbal or text-based warfare that I started making the weapon works, like the sculptural sword and axe and the large green painting, called “Armoury”, which depicts a collection of medieval weapons. This also led to the steel frames for each of the paintings, which in my mind makes the paintings all part of this metallic armoury.

SS: And the absurdist elements you introduce into these histories, legal or not, are they used to further your own narrative or story-based elements that run through the exhibition?

NM: That’s right. I’m interested in introducing wobbly or unstable narratives into established and authoritative histories. The law provides a framework or jump-off point, but my own narratives often take over. There are a lot of noses in the show, for instance. Noses tend to wander away from their faces and end up all over the place (attached to axes, on the front cover of books). I think it’s part of this “undoing” of learned or stable or authoritative narratives (like the idea of the body as this stable, put-together assemblage, or the law as this cohesive, rational document). I’m unpicking all these tightly woven threads, legal or otherwise, and letting things unravel. The exhibition is really a constant play between binaries, between the authoritative language of legal words / aesthetics and the sloppy materiality of paint or the poetic possibility of words.

SS: Following on from my previous question, absurdism in this sense lends itself to the theatricality that runs through your work, and this is where we come to the masks and faces. Can you elaborate on these works, and the idea of the courtroom as a stage populated by fictional characters?

NM: Well firstly, courtrooms are inherently theatrical places where real life conflict plays out in performative ways. All this rage and jealousy and resentment and anger and violence of a real-life dispute (whether it’s a contractual disagreement, a divorce, an application for citizenship etc.) is channelled into the structured format of rational legal argument and due process. Instead of fighting in the street with weapons, the courtroom steps in to provide this space of word-based conflict. Then there are costumes (gowns and sometimes wigs) and a formalised way of speaking with deference (referring to the Judge as “Your Honour”) and the barristers referring to each other as “my Learned Friend”. Then there are various rules and regulations around what type of information can enter the court – the rules of evidence, for instance, are intended to only permit “rational” fact finding. There are always lots of arguments about what should and should not be permitted to come before the court. And all of this takes place in a carefully constructed architectural space, where the hierarchy of each person in the room is represented visually – i.e. the Judge is usually elevated above everyone else.

So it’s a clearly manufactured environment that doesn’t attempt to hide the fact that everyone is playing a role. I wanted to push this idea in the exhibition and create these visceral and sometimes abject faces that give a glimpse of the spectrum of human emotions and human scenarios that filter in and out of the courtroom. I also wanted to explore this idea of rationality and irrationality, and this elaborate fiction that you can keep the irrational out of the courtroom, out of the arguments and out of any decision-making process.

SS: How have artists like Daumier influenced your thinking when looking at both law and art as one? Various scrolls, judgements, etchings and medieval imagery seemed to play an integral role in the making of this exhibition.

NM: I wanted the exhibition to speak across time periods. The law is tied to history, to the history of previous judgments (i.e. “precedents” in the Common Law tradition) and to the history of the places where it developed. I’m fascinated by the people who lived through these histories. How might a person five hundred years ago have thought about the idea of “property”? Or the idea of “fairness”? Where are those ideas buried in the Settler legal system of Australia today? Settler law in Australia of course has its origins in England, so I’m interested in medieval imagery as it tells us a bit about what those historic bodies looked like. In terms of the theatre of the courtroom, a lot of the performative courtroom rituals we use today and legal aesthetics more generally are visible in medieval scrolls and etchings.

In terms of Daumier, who you mention, he was satirising or critiquing the political landscape and specific leaders of his day. His works would have meant something very different, I think, to his contemporary audiences. The political meanings would likely overshadow the visual elements. But for me, viewing the works around two hundred years after they were made, I’m not so much interested in the specific people he’s depicting, whether it was this or that French King or lawmaker. Rather, I’m interested in how he’s visually depicting political or bureaucratic or legal subject matter. There’s this one image called Gargantua, which depicts a giant King Louis Philippe sitting on a throne, with a long ramp coming out of his mouth. All these bureaucrats are climbing up the ramp and into his mouth to feed him sacs full of tributes and goodies and he’s defecating out awards and medals. It’s just such a wonderful image, grotesque and elegant and funny. It kept popping into my mind while I was preparing for the show. I can’t say exactly how it influenced the exhibition, but it was one the ingredients in the mix.

SS: For some time now, the written word has played an integral part in your work. I’m thinking about your book The Knees and Ankles of a Landlord or your text pieces for Running Dog. But for The Plaintiff’s Third Face, the physical texts in the show are more modest, or nuanced. You have included books in the show, but the pages are glued shut and can’t be read. They only provide a title and physical clues about what’s inside. When text is visible, it’s usually quite small or installed close to the ceiling and nearly unreadable. What are you asking of the viewer when making these decisions?

NM: The text pieces reference a broader fictional universe beyond the physical works in the gallery. I wanted to give the impression that this world I am describing, which is partly real and partly imagined, is out there somewhere beyond the walls of the gallery. And I think the text works help with that, as they give a sense of authenticity and realism to the world-building. I worked with bookbinder Phil Ridgway to create three books: Faces: A Regulatory Guide, A Quorum of Noses and The Slipping Eyebrows and Other Sweat-Based Courtroom Scenarios. The books look like they could almost be real, they have these proper-looking old stamps and debossed gold-foiled text titles. Faces: A Regulatory Guide is actually a modified book of real court reports, which has been worn and aged to appear like it’s this antiquated legal object, something you might stumble across in a dusty second-hand bookstore. So, to answer your question, I’m asking the viewer to step into a world where these titles exist, even just for a moment. And to imagine what is inside the books, rather than being able to actually flick through them. I also wanted to make sure that all the works in the show speak to each other. The judgment, for instance, references the books and the books reference the masks and so on. I wanted to create this sense of a polyphonic choir of voices all speaking at once.